A Brief History of Luke Cage and America

Luke Cage is amazing. There, I said. If you watched it, you’ve probably said it. Critics have said it. And if you haven’t watched it yet, go ahead and do so. I guarantee you that you’ll say it, as well. (The dialogue might seem kind of hokey at first, but soon it becomes as natural to Luke Cage’s world as the quick-talking dialogue in the rest of the Marvel Cinematic Universe).

But what about Luke Cage makes him such a winner? The obvious answer is that it’s about time that we’ve gotten a person of color as a lead superhero. Don Cheedle/Terrence Howard might have made a great War Machine. Anthony Mackie might have made a great Falcon. In DC’s upcoming Justice League, Ray Fisher will make for what I’m sure is a solid Cyborg. This is all great. However one thing that all of these movies share in common is that the people of color in them are not leading characters.

As in virtually all superhero movies, they’re supporters. Wingmen. Assistants. Friends. The spotlight’s not on them. Sure, Cyborg is set to get his own movie in 2020, but come on–that’s 4 years away. Meanwhile, Black Panther is slated to get his own movie in 2018. These are all great steps in the right direction. But when we’re talking about the present, the now, the right-here–Luke Cage is the only superhero of color to have is own widely disseminated TV show. And it’s a well-written TV show, at that.

Unlike the adrenaline-pumping action tempo of Daredevil, Luke Cage opts for the more subtle character development peppered with violence. The characters are complex, their stories are moving, and there’s also the timing of it all. In a world where people of color are unfairly targeted, persecuted and shot, we get Luke Cage. A black man who is bullet-proof, is struggling to control his pent-up anger, and has a big heart.

In order to understand Luke Cage’s appeal today, we have to understand how the hero has figured in to the American narrative over the past forty plus years. Don’t worry. We’ll move quickly.

1972

Luke Cage was born in a year of tumult.

In 1972, America got the beginning of the Watergate Scandal. It got Nixon and Kissinger saying screw you to the Peace Accords in progress for Vietnam War by dropping the payloads of a fleet of B-52 bombers. It got the 1972 Munich Olympic terrorist attacks. It got hippies.

In 1972, America finally got around to the passing of the Equal Rights Amendment, which made it illegal to discriminate in employment based on sex (never mind that since the first seven-year span of it, it hasn’t been renewed as a part of our Constitution).

In 1972, America got Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education which backed up school integration. It got the final years of the Black Panther parties operation in Algeria, while numerous Black Panther Party members won a number of small public official positions in Oakland.

In 1972, America had a tumultuous year. But isn’t every year tumultuous. Isn’t this year tumultuous?

It’s not just the tumult that matters, it’s how the dust settles afterward. In 1972, the settling dust revealed growing black power in the US and a simultaneous distrust of the white bread-and butter patriarchy that had so long maintained the status quo.

In 1972, America got Luke Cage: Hero for Hire (#1).

Written by three white guys and predicated on the blaxploitation films of the day, Luke Cage didn’t necessarily have the most immaculate birth. Yes, a black character started to make a splash in the Marvel Universe. Yes, he kicked butt. But for the above stated reasons, this Luke Cage was based on a fad of cultural appropriation. Nothing against the original writers, but given how removed they were from the circumstances of the character, you can’t help but cringe a little.

Luke Cage later gets dubbed Luke Cage, Power Man in issue #17. One of his catch phrases is “Sweet Christmas”.

1978

In 1978, America got the world’s first cellular phone. It got the serial killer “Son of Sam” convicted of murder. He got a 25-year prison sentence. In 1978, America got Saturday Night Fever and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

In 1978, blaxploitation was waning in popularity. So were kung fu movies. What does Marvel do? They take their blaxploitation character (Luke Cage, Power Man) and partner him up with their kung fu superhero (Iron Fist). Although their respective genres lost their popularity, the two characters still firmly latched onto their corresponding tropes.

It wasn’t until Christopher Priest (a black writer) started writing for the series in 1985 and 1986 that any notable attempt was made to faze out the old-fashioned blaxploitation tropes.

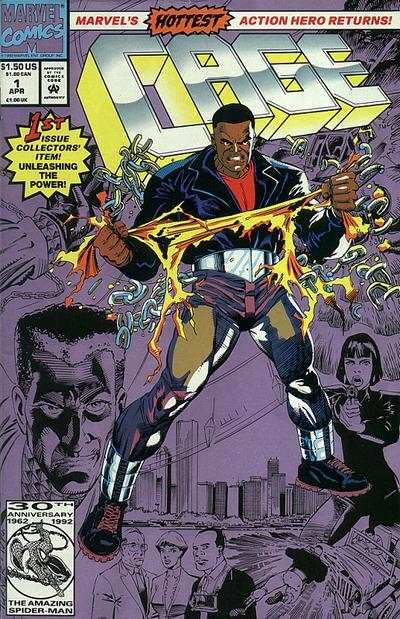

1992

In 1992, America got Bill Clinton as its 42nd president. It got Aladdin and Sister Act. It got Michael Jordan and Scotty Pippin winning the NBA Championship for the Bulls. It got the premier of “Barney and Friends”. In 1992, America got its first dosage of police brutality caught on tape. It got the Rodney King riots.

In 1992, Luke Cage gets rebranded as Cage. Instead of stomping around New York saying “Sweet Christmas”, he’s now tearing up his original costume in Chicago. Marcus McLaurin (a black writer) writes 20 great issues, before the series is canceled.

Over the next several years, Luke Cage will appear in a number of other comics, books, and tv shows, but only as a wingman–never as the sole hero.

2016

In 2016, America has one of the strangest elections in the country. It has Google Cardboard and PS4 and Xbox One. It has PokemonGo. In 2016, America has rampant gunmen. It has police brutality caught on body-cam and iPhone. It has the Black Lives Matter Movement. In 2016, America has Stranger Things and The Get Down on Netflix. It also has Luke Cage.

How will the dust settle at the end of this year? A lot more tumult will happen before this year is officially done. What will the result be? One thing is that we’re finally getting a superhero show about a person of color. This is good. But there’s still a lot of ground to cover. We still need more superheroes of color. We still need more female superheroes. We also need a lot of things in the real world too. Having these wins reflected, predicted, and demanded in the media that we consume can help that out.